|

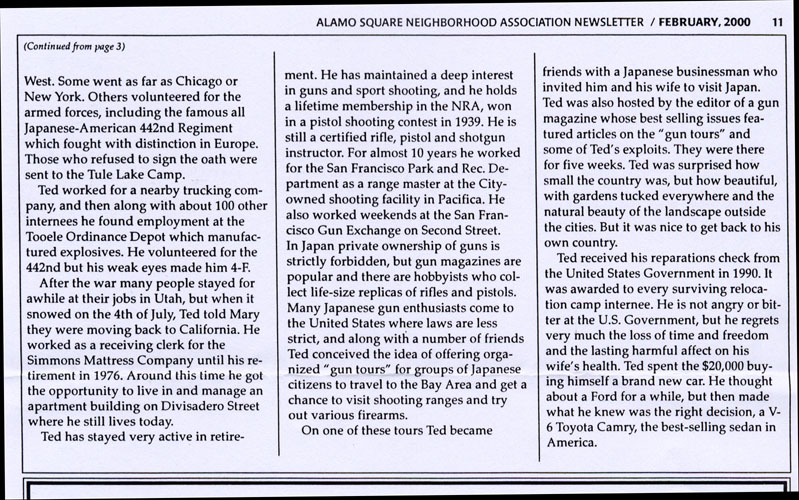

This newsletter gives the photographer's full name as Tsunekicki

Imai. It is the story of Ted Imai, son of the photographer,

but it also provides us background information on T. Imai...

Forward:

The vast majority of the information in this article

comes from Ted Imai, now 95, the photographer’s only son. Like most

memories from long ago, Ted’s are sometimes indistinct, disjointed

and even contradictory, and they may derive from family tradition,

not fact. I did some research at San Francisco’s Japanese American

History Archives with the assistance of Mr. Seizo Oka, community

historian and executive director of the archives (recently diseased)

and at the S.F. Public Library. I intend in the future to consult

with other members of the Imai family who may have more or different

information, and I would also like to try to find experts in

historic photography to take a in depth look at the “Night Time

Cloud Effect” photo. So this is a work in progress.

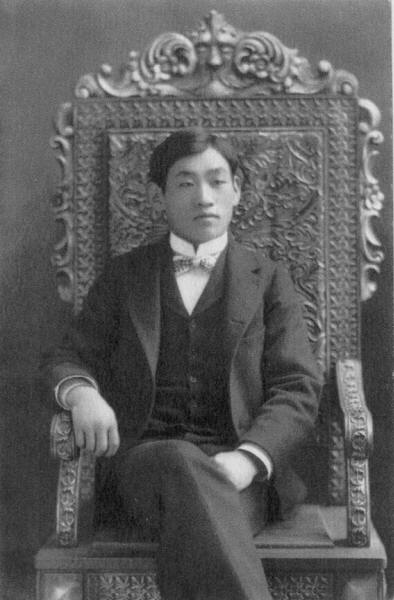

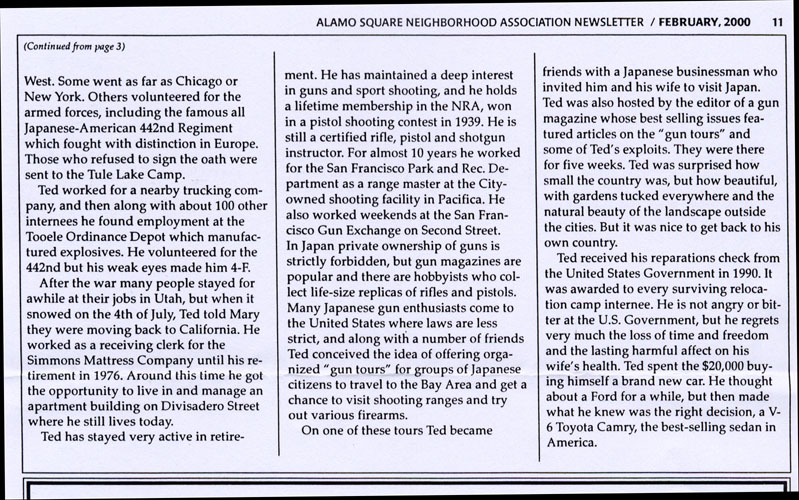

Tsunekichi Imai

Tsunekichi Imai, who created what is probably the best known

photographic image of the third Cliff House (1896-1907), was

according to his family and other sources, the first Japanese

commercial photographer in San Francisco. He operated a studio at

1303 Polk Street, near Bush, (cited in the Japanese Yearbook of

1905) and later at 1950 Bush Street, which also served for many

years as the Imai family home.

Born in 1872 in Yamaguchi, an agricultural region on

the island of Honshu in southern Japan, he learned his craft in his

native country and then in 1899 immigrated to United States.

Economic conditions in Japan were difficult, and Tsunekichi Imai was

part of large wave of workers who were drawn to California because

of an acute labor shortage caused by the imposition of the Chinese

Exclusion Act which had cut off the supply of immigrant Chinese

workers. He may have thought that a burgeoning Japanese community

would be well served by its own photographer.

Originally Tsunekichi Imai planned to save the money he

made and return to Japan, but with each child born in the United

States this prospect seemed to grow dimmer. He and his wife, Taki,

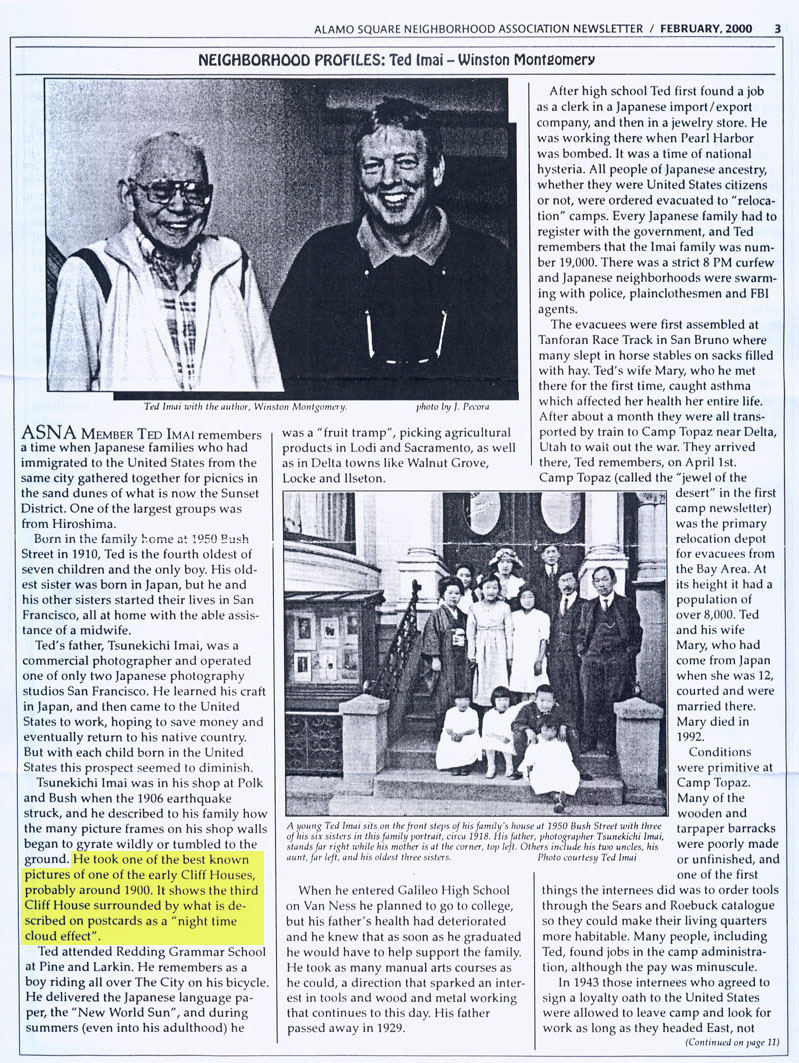

eventually had seven girls and one boy. Ted (originally Heiyu) Imai,

born in 1910, is the second oldest child and the first to be born in

the United States. One daughter died at about seven years of age

from acute appendicitis.

Tsunekichi Imai was working in his Polk Street studio

when the 1906 earthquake struck, and he described to his family how

the pictures hanging from his shop walls shook and gyrated wildly,

many tumbling to the ground. In the days that followed, the rapidly

spreading fire which followed the quake overwhelmed firefighters and

threatened to destroy the entire city. To stop the fire by depriving

it of fuel, officials decided to create a firebreak by dynamiting a

swath of buildings east of Van Ness Avenue. The Imai studio was

located in one of these buildings.

The structures to be exploded were evacuated hurriedly

and Tsunekichi Imai thought that all his equipment and furniture had

been lost. Someone suggested that he go up to Lafayette Park at

Washington and Laguna streets, and there he discovered stacks of

personal possessions and household furnishings covered by tarpaulins

that firemen and other volunteers must have rescued from the doomed

buildings. He found most of the things from his shop piled together

and even labeled with his name. Ironically many of the photographs

and other personal affects that survived the earthquake and fire

were lost during the period that the Imai family was interned during

W.W. II at Camp Topaz in Utah.

Tsunekichi Imai took a number of photographs in the

earthquake’s aftermath, the most notable, according to his son, Ted,

showed a man trapped on the upper balcony of a burning building

pleading for help as the flames engulfed him. The picture was taken

just as soldiers on the ground shot the man with their rifles to put

him out of his misery. Ted says his father was fearful of the

possible legal implications of taking this photo or even witnessing

this event, and eventually destroyed it.

Ted, who as a young boy often acted as his father’s

assistant, has a vivid memory of other photographs his father took.

When the 1918 influenza epidemic struck San Francisco (doing

particular damage in the Japanese community) his father was busy

around the clock taking photographs of the victims to send back to

their relatives in Japan. The Japanese in San Francisco were served

chiefly by the Martin and Brown Funeral Home on Sutter St. One

particularly poignant image Ted recalls was of a mother with her

infant in her arms, both sharing the same coffin.

Tsunekichi Imai also was commissioned to do a photographic portrait

of the colorful early California literary figure, Joaquin Miller,

the so-called “poet of the Sierras”. A friend of Jack London and

Ambrose Bierce, Joaquin Miller in his later years was a resident of

the Oakland Hills and his forested 75 acre estate which he called

“The Hights” is now a park. Ted Imai believes an original print of

this photo is still in the possession of the Imai family.

Another portrait of a dignitary that Tsunekichi Imai crafted was of

Prince Fushimi (Hiroyasu), a member of the Japanese Imperial Family.

The City of San Francisco has always had a close relationship with

Japan, --the first visit of a Japanese warship to San Francisco was

in 1860, and the tradition of naval visits to San Francisco

continued until the First World War.

Every two years the Japanese Training Squadron on their

Sea Cadet graduation cruise would lay anchor in San Francisco. Like

this era’s Fleet Week, the ships, mostly old battleships, were open

to the public, and in San Francisco and the East Bay there were

welcoming ceremonies and exhibitions of Japanese arts and culture

including sumo wrestling, martial arts and fencing. The ships gave

away small Japanese flags and other souvenirs. Ted Imai, like all

Japanese American kids, was tremendously excited. The culmination of

the events was a huge parade down Market Street in San Francisco.

Tsunekichi Imai took photos of many of these events and

he was invited to attend the banquet in honor of the Japanese guests

which was sponsored by the Japanese American Association. This was

held at some of San Francisco’s most prestigious hotels including

the Fairmount and the St. Francis. Tsunekichi Imai always sat at a

table with the teenage cadets and their training officers and since

they had not traveled much out of their country or had much

familiarity with western cuisine they looked to him for clues as how

to behave. There was a bowl of olives on every table and throughout

the meal there was much discussion as to their nature and purpose.

As the table was being cleared and coffee served, Tsunekichi Imai

grabbed a handful of olives and dropped them into his cup. All the

Japanese cadets and officers immediately followed suit.

It was probably in 1904 that Tsunekichi Imai took the

portrait of Prince Fushimi, an Admiral in the Japanese Navy, a

member of the Japanese Supreme War Council and Chief of the Japanese

Naval General Staff from 1932 to 1941. At the Japanese American

History Archives in San Francisco there is a picture of the Prince

on a visit to San Francisco in 1904. In gratitude for the portrait

Prince Fushimi gave the photographer a silver cloisonné cigarette

case and a sterling silver matchbox. These gifts are still in

possession of the Imai family.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Imai

family, afraid that their loyalty to the United States would be

questioned if this portrait were discovered in their home,

transported the original print to the Japanese Consulate in San

Francisco, from which it disappeared.

According to Ted Imai, the most interesting fact about his father’s

photograph of the Cliff House, sometimes called “Nighttime Cloud

Effect” is that it was essentially a fake, created or at least

substantially enhanced in the studio. Ted was not born until after

the picture was taken, but his father over the years told him that

he had shot the photo in broad daylight and then gradually darkened

it over a period of 4 or 5 days, retouching it and redeveloping it

by trial and error until he had achieved the desired image. Ted does

not remember the specific processes or chemicals his father used. In

support of this theory Ted says that such an exposure would have

been impossible to create with the primitive cameras of the time and

flash powder, the only supplemental illumination then available to

photographers.

Ted remembers that his father had a very well equipped

studio for his time, including a custom built 4 ft by 4 ft enlarger

he utilized to print his portraits. It featured a 1000 watt light,

immensely powerful for its time.

Some observers see a bolt of lightning in the photograph, but upon

closer examination it appears to be the edge of a backlit cloud. I

have no reason to doubt Ted Imai’s memory but at least one

knowledgeable photographer says it appears authentic. In reply to my

inquiry, Haral Edens, a doctoral candidate in atmospheric psychics

at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, an experienced

weather photographer and proprietor of

www.weather-photography.com states as follows:

“I’m almost sure that that photo is real. There is no lightning

in the photo however; the streak of light going to the upper left is

a so-called silver lining effect. You can also see the shadow of

that cloud to its right, cast on another cloud (the sun must have

been left of the photo). No-one would produce that shadow effect in

a studio, since it is little interesting. I think that that gives a

clue that the scenery has not been edited or created.”

Obviously more investigation on how this photo was

created remains to be done, but it is possible that a daytime photo

containing an unusual configuration of light and cloud was

strategically darkened to make it appear that it was taken at night.

The lights or reflections of light in the lower windows of the Cliff

House probably would be relatively easy to add.

Some of the existing prints of “Nighttime Cloud Effect”

have “Imai” written in ink diagonally across the right hand corner.

From 1985 a version of this photograph without “Imai” has been

featured on the cover of Marilyn Blaisdell’s “San Francisciana:

Photographs of the Cliff House”. Originally the photographer was

unnamed but the Imai family was able to prevail upon the publisher

to add T. Imai to the list of credits. There is another photograph

in that book, “Tea House and Lunch Stand, Cliff House Terrace” (page

49) which Ted Imai remembers his father taking. In fact he remembers

acting as his father’s helper that day and carrying the photo plates

in a leather case.

As to the small, cardboard framed souvenir version of

the photo which features on the reverse side the fanciful, but

racially stereotyped description of how the photo was taken, my copy

of that photo features the ink stamp of the store which most likely

sold it.

|

|

This was an obviously Japanese store and was listed in the San

Francisco City Directory beginning in 1901 and ending, ominously, in

1941. The fact that the photo was sold in a Japanese store and that

the account of its origin contains an element of truth and supports

the reported fiction of its night time creation leads me to believe

that the caption was written with the assent and knowledge of the

photographer. Tsunekichi Imai and the retailers he used probably

thought that a sympathetic and inspirational story would make the

photo more saleable.

Ted Imai says (and the story about the olives

reinforces this) that his father was an inveterate practical joker

so this mythical story behind the photo probably appealed to him

greatly. However, he was not fluent in English, and someone else

would have had to do the actual composition.

Tsunekichi Imai was a creative man of many talents and artistic

interests. He was formally trained in Japan in flower arrangement

and he was a bonsai enthusiast and avid gardener. In the backyard of

the family home at 1950 Bush he designed and built a traditional

style Japanese Tea Garden with a ornamental fish pond and a tea

house custom built by a local Japanese carpenter featuring finely

crafted sliding shoji doors.

Tsunekichi Imai visited Yosemite often with his family

and he came to admire highly an interestingly shaped boulder in the

park. When his tea garden neared completion he recruited a friend

who worked at Pacific Laundry and they drove the company’s Model T

panel truck to Yosemite and brought the four or five hundred pound

stone back with them. When the Imai’s moved from 1950 Bush a

neighbor moved it to his own yard.

Tsunekichi Imai died in 1929.

Winston Montgomery

Addendum: Ted’s Photos Returned

There is another interesting story concerning the

history of the Imai family and photographs taken by Tsunekichi Imai.

Soon after I visited the Japanese American History Archive a few

years ago, I was contacted by Kimi Wood, a San Francisco native

living in Redwood City. She had visited the Archives to try to find

out if anyone with the surname Imai was still living in San

Francisco. They would have to be quite elderly by this time, she

thought. She was in possession of some old glass plates and photo

albums that were marked with the name Imai.

Kimi’s parents had lived in Japan for a number of years

after the Second World War where her father was in the U.S. Armed

Forces and her mother had taught English to Japanese women. During

their stay in Japan they developed a tremendous affection and

respect for the Japanese people and culture, hence their daughter

Kimi’s name. Back in the United States in the late 1960’s some

friends were renting an apartment at 2025 Pine Street near Japantown

and discovered a cache old photos concealed in a joist space in the

garage. They turned them over to Kimi’s mother because they knew of

her strong interest in Japan.

Over 30 years later when Kimi was helping her mother

pack up her possessions to move she came across the photographs and

decided to see if she could locate their owners. Kimi had done

genealogical research before, including working on the Mormon lists.

One of her first investigative forays was to the Japanese American

History Archives where Mr. Oka told her that someone else had just

been in seeking information about the Imai family. Ted and Kimi were

introduced and his family photos returned to him. Ted remembered

them specifically (in fact they were mostly of him as a child since

as the only boy and highly photogenic he was his father’s favorite

subject. Ted’s description of why they were hidden in the garage

gives a vivid picture of the chaotic and desperate days before the

Japanese were forced to get on buses and leave San Francisco. Since

they could take very little to the internment camps, families faced

the problem of what do with their personal possessions. Warehouses

and furniture storage facilities filled up quickly and many families

were left with no way to protect their furniture and personal items.

Some unscrupulous people took advantage of this situation by going

from house to house in Japantown offering to buy people’s furniture

for pennies on the dollar, Ted remembers, and some of the Japanese

got as much as they could for their stuff, but others attempted to

conceal things in their house or on their property. Most items were

never seen again.

Ted tells of entire automobiles being buried in

backyards, tools and other valuables hidden under floorboards and

personal possessions crammed in crawlspaces or behind attic rafters.

Ted Imai hid some of his machine tools under the floor in his

basement, but they were gone when he returned. This is how the

photos ended up concealed in the garage at 2025 Pine Street, the

house that the Imai family moved to sometime in the 1930’s (they

were renters) when 1950 Bush Street was sold to a local Japanese

doctor.

Winston Montgomery, a

longtime San Francisco resident, is a retired painting and

plastering contractor who is re-inventing himself as a songwriter.

You can listen to his songs at

www.wmontgomerysongs.com or send him an email at

winpegg@att.net.

|

.jpg)

.jpg)